“Incredible Black Women You Should Know About” – The Series

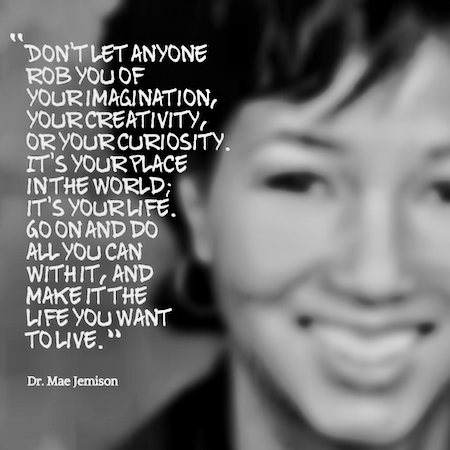

Mae Jemison

“First African American women in Space”

(Oct. 1, 1956 –)

By DonnaMarie Woodson

This article, from the May 2022 edition of the Charmeck Chronicle, is published here with permission of the author.

Researching the story of Mae Jemison is so inspiring and one of the reasons I love to write; learning the biographies of remarkable people. Some known and others I didn’t realize their impact on our shared history.

Meet Mae Carol Jemison, an American engineer, physician, and former NASA astronaut. Jemison was chosen for NASA’s astronaut program in 1987, becoming the first Black woman to travel in space after launching with the Space Shuttle Endeavour crew in 1992. The team made 127 orbits around the Earth and returned to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on September 20th, 1992. The Associated Press covered her as the “first Black woman astronaut” in 1987.

Afraid of heights, she nevertheless logged 190 hours, 30 minutes, and 23 seconds in space, NASA said.

Mae Jemison has always reached for the stars. Born in Decatur, Ala., her mother was the youngest of three children, an elementary school teacher, and her father was a maintenance supervisor. A few years after she was born, Jemison and her family moved to Chicago.

In addition to her love for dance, Jemison knew that she wanted to study science at a very young age. She grew up watching the Apollo airings on TV, but she was often upset that there were no female astronauts. She later recalled, “Everybody was thrilled about space, but I remember being really irritated that there were no women astronauts.”

Inspired by African American actress Nichelle Nichols, who played Lieutenant Uhura on the Star Trek television show, Jemison was determined to one day travel in space.

Jemison enjoyed studying nature and human physiology, using her observations to learn more about science. Although her mother encouraged her curiosity and both her parents were supportive of her interest in science, she did not always see the same support from her teachers. When Jemison told a kindergarten teacher she wanted to be a scientist when she grew up; the teacher assumed it meant she wanted to be a nurse.

In 1973, she graduated from Morgan Park High School when she was only 16. Once she graduated, Jemison left Chicago to attend Stanford University in California. Jemison graduated in 1977 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Chemical Engineering and a Bachelor

After graduating from Stanford University, Jemison attended Cornell Medical School. While in medical school, she traveled to Cuba to lead a study for the American Medical Student Association. She also worked at a Cambodian refugee camp in Thailand.

Jemison graduated from Cornell with a Doctorate in Medicine in 1981. Shortly after her graduation, she became an intern at the Los Angeles County Medical Center and practiced general medicine. Fluent in Russian, Japanese, and Swahili, Jemison joined the Peace Corps in 1983 and served as a medical officer for two years in Africa.

Upon returning to the United States after serving in the Peace Corps, Jemison settled in Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, she entered into private practice and took graduate-level engineering courses. However, the flights of Sally Ride and Guion Bluford in 1983 inspired Jemison to apply to the astronaut program.

Jemison first applied to NASA’s astronaut training program in October 1985, but NASA postponed the selection of new candidates after the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986. Jemison reapplied in 1987 and was chosen out of roughly 2,000 applicants to be one of the fifteen people in the NASA Astronaut Group 12, the first group selected following the explosion of the Challenger.

Jemison flew her only space mission from September 12th to 20, 1992, on STS-47, a cooperative mission between the United States and Japan and the 50th shuttle mission. Jemison logged 190 hours, 30 minutes, and 23 seconds in space and orbited the Earth 127 times.

STS-47 carried the Spacelab Japan module, including 43 Japanese and United States life science and materials processing experiments.

Jemison and Japanese astronaut Mamoru Mohri were trained to use the Autogenic Feedback Training Exercise (AFTE), a technique developed by Patricia S. Cowings. The technique uses biofeedback and autogenic training to help patients monitor and control their physiology as a possible treatment for motion sickness, anxiety, and stress-related disorders. (In 1999, Jemison founded BioSentient Corp and obtained the license to commercialize AFTE, the technique she and Mohri tested on themselves during STS-47.)

The crew split into two shifts, with Jemison assigned to the Blue Shift. Throughout the eight-day mission, she began communications on her shift with the salute “Hailing frequencies open,” a quote from Star Trek. Jemison took a poster from the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater along with her on the flight. She also took a West African figurine and a photo of pioneering aviator Bessie Coleman, the first African American with an international pilot license.

Jemison left NASA in 1993 after serving as an astronaut for six years. Jemison served on the World Sickle Cell Foundation board of directors from 1990 to 1992. In 1993, she founded The Jemison Group Inc., a consulting firm that considers the socio-cultural impact of technological advancements and design.

Jemison also founded the Dorothy Jemison Foundation for Excellence and named the foundation in honor of her mother. One of the foundation projects is The Earth We Share, a science camp for students 12 to 16. The camps were founded in 1994 and were held at Dartmouth College, Colorado School of Mines, Choate Rosemary Hall, and other sites in the United States and internationally in South Africa, Tunisia, and Switzerland.

In 2001, she went on to write her first book, “Find Where the Wind Goes,” which was a children’s book about her life.

The Dorothy Jemison Foundation sponsors other events and programs, including the Shaping the World essay competition and Listening to the Future (a survey program targeting obtaining opinions from students). Earth Online (an online chatroom that allows students to communicate and discuss ideas on space and science safely), and the Reality Leads Fantasy Gala.

Jemison was a professor of environmental studies at Dartmouth College from 1995 to 2002, where she directed the Jemison Institute for Advancing Technology in Developing Countries. In 1999, she became an Andrew D. White Professor-at-Large at Cornell University. Jemison advocates strongly in favor of science education and getting minority students interested in science.

Levar Burton learned that Jemison was an avid Star Trek fan and asked her if she would be interested in being on the show. In 1993, Jemison appeared as Lieutenant Palmer in “Second Chances,” an episode of the science fiction television series Star Trek: The Next Generation, becoming the first real-life astronaut to appear on Star Trek.

Currently, Jemison is leading the 100 Year Starship project through the United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). This project works to make sure human space travel to another star is possible within the next 100 years.

Jemison is an active public speaker who appears before private and public groups promoting science and technology. “Having been an astronaut gives me a platform,” says Jemison, “but I’d blow it if I just talked about the Shuttle.” Jemison uses her platform to speak out on the gap in health care quality between the United States and the Third World, saying that “Martin Luther King [Jr.] … didn’t just have a dream, he got things done.”

In May 2007, she was the graduation commencement speaker and only the 11th person in the 52-year history of Harvey Mudd College to be awarded an honorary degree. And Jemison participated with First Lady Michelle Obama in a forum for promising girls in the Washington, D.C. public schools in March 2009.

Jemison is a member of the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Medicine, inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame, National Medical Association Hall of Fame, and Texas Science Hall of Fame. She has received multiple awards and honorary degrees, including the National Organization for Women’s Intrepid Award and the Kilby Science Award. She currently lives in Houston, Texas.

Works Cited:

National Women’s History Museum