“Incredible Black Women You Should Know About” – The Series

If I hear “Critical Race Theory” one more time, I’m going to scream! Teaching a class on this scholarly investigation of the intersectionality of law and race is not a thing. Since 2020, conservative U.S. lawmakers have sought to ban or restrict studies of America’s Racial History citing “Critical Race Theory” instruction along with other anti-racism programs as the problem. My criticism of these efforts is that the goal of the laws is to more broadly silence discussions of racism, equality, social justice, and the history of race. We need to tell the whole story and not just the parts conservatives feel are permissible to teach. So, in the spirit of all American History, I’ll be featuring the stories of Black Women who you may or may not know about. These worthy trailblazers excelled in fields that, until they made their mark, had been off-limits to black women. I hope you enjoy this series, beginning with:

The First Published Poet

Phillis Wheatley

By DonnaMarie Woodson

This article, from the September 2021 edition of the Charmeck Chronicle, is published here with permission of the author.

Although the date and place of her birth are not documented, scholars believe that Phillis Wheatley was born in 1753 in West Africa, most likely in present-day Gambia or Senegal. She was sold by a local chief to a visiting trader, who took her to Boston in the British Colony of Massachusetts, on July 11, 1761. On arrival in Boston, she was bought by the wealthy Boston merchant and tailor John Wheatley as a slave for his wife Susanna. John and Susanna Wheatley named her Phillis, after the ship that had transported her to America. She was given their last name of Wheatley, as was a common custom if any surname was used for enslaved people.

The Wheatleys’ 18-year-old daughter, Mary, was Phillis’s first tutor in reading and writing. Their son, Nathaniel, also helped her. John Wheatley was known as a progressive throughout New England; his family afforded Phillis an unprecedented education for an enslaved person, and one unusual for a woman of any race.

By the age of 12, she was reading Greek and Latin classics in their original languages, as well as difficult passages from the Bible. At the age of 14, she wrote her first poem, “To the University of Cambridge [Harvard], in New England”. Recognizing her literary ability, the Wheatley family supported Phillis’s education and left household labor to their other domestic enslaved workers.

The Wheatleys often showed off her abilities to friends and family. Strongly influenced by her readings of the works of Alexander Pope, John Milton, Homer, Horace, and Virgil, Phillis began to write poetry.

Publication of “An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of the Celebrated Divine George Whitefield” in 1770 brought her great notoriety.

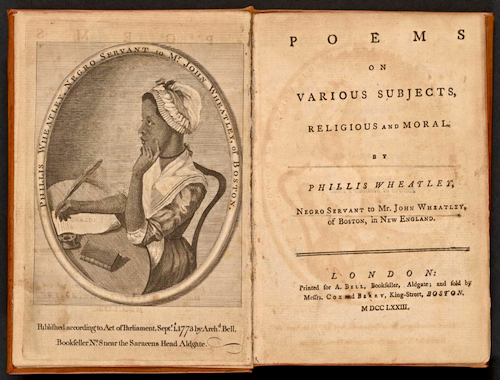

In 1773, with financial support from the English Countess of Huntingdon, Wheatley traveled to London with the Wheatleys to publish her first collection of poems, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral” – the first book written by a black woman in America. It included a forward, signed by John Hancock and other Boston notables – as well as a portrait of Wheatley – all designed to prove that the work was indeed written by a black woman. The Wheatleys emancipated her shortly thereafter.

Wheatley’s poems reflected several influences on her life, among them the well-known poets she studied, such as Alexander Pope and Thomas Gray. Pride in her African heritage was also evident. Her writing style embraced the elegy, likely from her African roots, where it was the role of girls to sing and perform funeral dirges.

Religion was also a key influence, and it led Protestants in America and England to enjoy her work. Enslavers and abolitionists both read her work; the former to convince the enslaved population to convert, the latter as proof of the intellectual abilities of people of color.

During the American Revolution, Wheatley’s opposition to slavery heightened. She wrote several letters to ministers and others on liberty and freedom. During the peak of her writing career, she wrote a well-received poem praising the appointment of George Washington as the commander of the Continental Army. However, she believed that slavery was the issue that prevented the colonists from achieving true heroism.

In 1778, Wheatley married John Peters, a free black man from Boston with whom she had three children, though none survived. In 1779, Wheatley issued a proposal for a second volume of poems but was unable to publish it because she had lost her patrons after her emancipation; publication of books was often based on gaining subscriptions for guaranteed sales beforehand. The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) was also a factor. However, some of her poems that were to be included in the second volume were later published in pamphlets and newspapers.

To support her family, she worked as a scrubwoman in a boardinghouse while continuing to write poetry. Wheatley died in December 1784, due to complications from childbirth. In addition to making an important contribution to American literature, Wheatley’s literary and artistic talents helped show that African-Americans were equally capable, creative, intelligent human beings who benefited from an education. In part, this helped the cause of the abolition movement.

In “The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America’s First Black Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers” by Henry Louis Gates Jr., he writes about how Phillis Wheatley literally wrote her way to freedom when, in 1773, she became the first person of African descent to publish a book of poems in the English language. The toast of London, lauded by Europeans as diverse as Voltaire and Gibbon, Wheatley was for a time the most famous black woman in the West.

Though Benjamin Franklin received her, and George Washington thanked her for poems she dedicated to him, Thomas Jefferson refused to acknowledge her gifts.

“Religion, indeed, has produced a Phillis Wheatley,” he wrote, “but it could not produce a poet.” In other words, slaves have misery in their lives, and they have souls, but they lack the intellectual and aesthetic endowments required to create literature.

[Gates’] book explores the pivotal roles that Wheatley and Jefferson have played in shaping the black literary tradition. He debates the issues that fermented around Wheatley in her day and illustrates the peculiar history that resulted in Thomas Jefferson’s being lauded as a father of the black freedom struggle and Phillis Wheatley’s vilification as something of an Uncle Tom.On July 16, 2019, at the London site where A. Bell Booksellers published Wheatley’s first book in September 1773 (8 Aldgate, now the location of the Dorsett City Hotel), the unveiling took place of a commemorative blue plaque honoring her, organized by the Nubian Jak Community Trust and Black History Walks.

NJCT is a commemorative plaque and sculpture scheme founded by Jak Beula that highlights the historic contributions of Black and minority ethnic people in Britain. The first NJCT heritage plaque, honoring Bob Marley, was unveiled in 2006 with an intention to commemorate and celebrate the diverse history of modern Britain. Its objectives include the promotion of social equality and to encourage activities that promote cultural diversity in society.

Works Cited:

- CNN, “10 incredible black women you should know about“.

- National Women’s History Museum, Biography of Phillis Wheatley, Edited by Dr. Debra Michals, 2015.

- Wikipedia, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral“

- Wikipedia, “Critical Race Theory“

- Wikipedia, “Nubian Jak Community Trust“