The civic holidays and religious holy days that span from Thanksgiving to New Year’s Day turn Americans’ attention to people in need. A glossary of phrases signifies the season: Angel Tree, Advent Giving Tree, Toys for Tots, Coats for Kid, Food Bank, Giving Tuesday.

The rush to buy runs parallel to the impulse to give. The season is characterized by both consumerism and charity — as well as by volunteerism. It is awesome to behold people who serve food to the hungry, who spend evenings supervising shelters for the homeless, who tutor struggling students, and who sort and distribute clothing.

Making holiday gifts of money to charities is splendid. Volunteerism is wonderful. And yet, however inspirational and important, individual initiatives cannot do all that needs to be done to reduce poverty, hunger, homelessness, and ill-health.

These difficult, complex tasks require strong societal institutions: organized philanthropy, research and advocacy non-profits, religious congregations, and more. These tasks also require a responsive government.

As North Carolina heads into a period of significant, substantial policy decisions for its schools, colleges, and universities, it is a moment to focus anew on the state’s long-standing, bipartisan consensus that has linked economic advancement to educational progress. Moving people out of poverty and from near-poverty into the middle class depends on job growth and on education that prepares young people for well-paying work.

Dry year-by-year economic data document the basic point: When employment rises, poverty declines. When recessions reduce employment, poverty increases.

In “A Christmas Carol,” the enduring morality tale written in the 1840s, Charles Dickens makes the economy-education linkage vivid in an encounter between Ebenezer Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Present. Scrooge notices “something strange” under the ghost’s cloak. Two children emerge.

In “A Christmas Carol,” the enduring morality tale written in the 1840s, Charles Dickens makes the economy-education linkage vivid in an encounter between Ebenezer Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Present. Scrooge notices “something strange” under the ghost’s cloak. Two children emerge.

“This boy is Ignorance,” says the ghost. “This girl is Want. Beware them both.”

The late William Winter, a former Mississippi governor who served for several years as chair of MDC, the Durham-based Southern think-tank, also saw clearly that society can’t reduce want without shrinking ignorance. Quoted in a State of the South report, Winter said, “The line that separates the well-educated from the poorly educated is the harshest fault line of all … The only road out of poverty runs by the schoolhouse.”

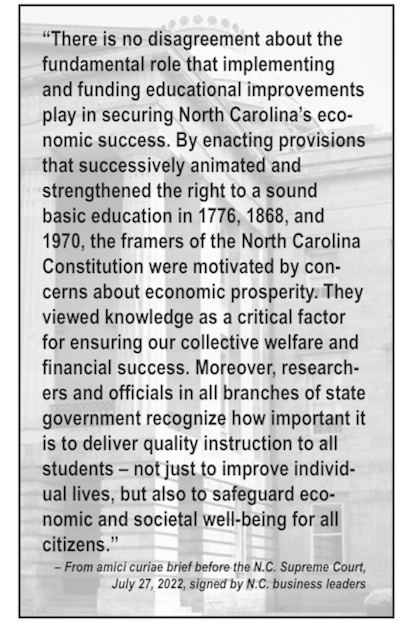

In a brief submitted to the state Supreme Court before its recent ruling to implement the right to a sound, basic education, 55 business men and women, some also with experience as civic leaders and political participants, expansively reiterated the traditional North Carolina understanding of the impact of education on individual economic well-being and the state’s economic advancement.

The state needs a workforce of skill and talent to support existing businesses and to attract investments, they say. To the justices, they express concern that “failing to implement improvements to North Carolina schools will negatively affect students’ ability to thrive in the workplace — and by extension our collective financial condition.”

“Education is the inexorable force that dictates the economic fortunes of our students and our collective citizenry,” says the business leaders’ brief. “Prosperity ebbs and flows with the tide of education, and time and tide wait for no one.”

North Carolina has, to be sure, several charter schools and private-parochial schools with a special mission to serve young people in economically distressed households and in neighborhoods and towns of concentrated poverty. The state benefits from their efforts and successes.

Still, it is the system of public education that has the scope and heft to attend to the education, nutrition, and emotional health of hundreds of thousands of young North Carolinians. From pre-K through higher ed, public education consists of societal institutions with overall capacity to alleviate poverty and propel upward mobility beyond the range of the charity and volunteerism that enliven the holidays and holy days.

– – –

Louisiana native John Ferrel Guillory was a working journalist for more than 25 years, at Newsday, the States-Item in New Orleans and then in Raleigh as the News & Observer’s chief NC Capitol correspondent, Washington correspondent, associate editor, government affairs editor and Southern correspondent. In 1995 he was writer in residence at MDC Inc., a Chapel Hill think tank focused on Southern economic and community development, and by 1997 he was director of the UNC Chapel Hill Program on Southern Politics, Media and Public Life. He is an emeritus Professor of the Practice of Journalism in UNC’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media. In 2014 he co-founded EducationNC, a statewide news and policy analysis website where this commentary was first published. The article is republished here under a Creative Commons license.